Two Muslim Moms, Their Sons, and Secret Girlfriends—And The Soulful Islamic Approach We’re Missing

Every so often, a video moves quietly through Muslim spaces and captures our collective attention —because it dares to touch what we often keep tucked beneath silence. Dating. Girlfriends. Premarital relationships. The tender and complicated realities that many Muslim families whisper about behind closed doors while their teenagers navigate them alone. These videos feel refreshing at first glance, almost relieving, because they promise honesty about the things our community labels as “taboo.”

Recently, I came across a video titled “How Two Muslim Moms Dealt With Their Sons’ Secret Girlfriends.” On the surface, it held the possibility of nuance. Two scenarios. Two families. Two sons crossing a boundary their parents had hoped they wouldn’t. It felt like an opening — perhaps an invitation to finally explore the emotional, developmental, and spiritual terrain that shapes why Muslim teenagers struggle in the first place. Not simply what they did, but what their actions meant. What needs they were trying to meet. What their hearts were aching for and didn’t know how to articulate.

Instead, what emerged was a pattern many of us know too well. The framework stays focused on behavior, rules, and consequences — a moral landscape drawn in sharp, rigid lines. Compassion is defined narrowly, through a theological lens of “guiding them back to what is permissible,” rather than through understanding the inner world of a young person trying to make sense of attraction, sexual desire, belonging, loneliness, and connection. Dating is presented as a moral violation to be corrected behaviorally, which ignores soul-based factors (i.e. sexual desire, emotions, etc) that require deeper inner work.

The stories are compelling, yes — and they are also incomplete. And what is missing matters deeply. Because at its heart, this blog post reaches for the layers beneath the surface of behavior — toward the nuanced, soul-rooted approaches our tradition actually offers. Approaches grounded in Islamic understandings of the soul (i.e. Islamic Psychology) and the Prophetic ways we are invited to hold human complexity.

These are the layers that shape how we respond to our children, how we understand their inner worlds, and how we help them cultivate a relationship with Allah that can hold them through the beauty and the struggle of being human.

The Issues We Need to Name Honestly

The video frames the two stories as a kind of morality tale about religious upbringing: the family that “failed” to teach the religion lost the ability to guide their son, while the family that prioritized Shariah and fiqh successfully led their son back to the “right choice.” The overt message is simple: if you instill knowledge early, your children will act correctly; if you don’t, you forfeit your influence.

But when we widen the lens, this logic breaks down. Both boys — the one raised with strong religious teachings and the one raised without them — made the same choice. Both sought companionship, intimacy, affection, and connection through a girlfriend. One acted without formal Islamic knowledge; the other acted despite it.

This alone should unsettle the neat conclusion the video draws, because it echoes a foundational Islamic psychology truth: behavior cannot be understood through the cognitive mind/knowledge alone. Allah reminds us of the inner complexity of the human being when He says, “Indeed, the nafs constantly urges toward what is harmful, except those upon whom my Lord has mercy.” (Qur’an 12:53) A young person’s choices arise from this interplay of inner forces — not only from what they know in their intellect, but from what their soul yearns for and what their heart leans toward.

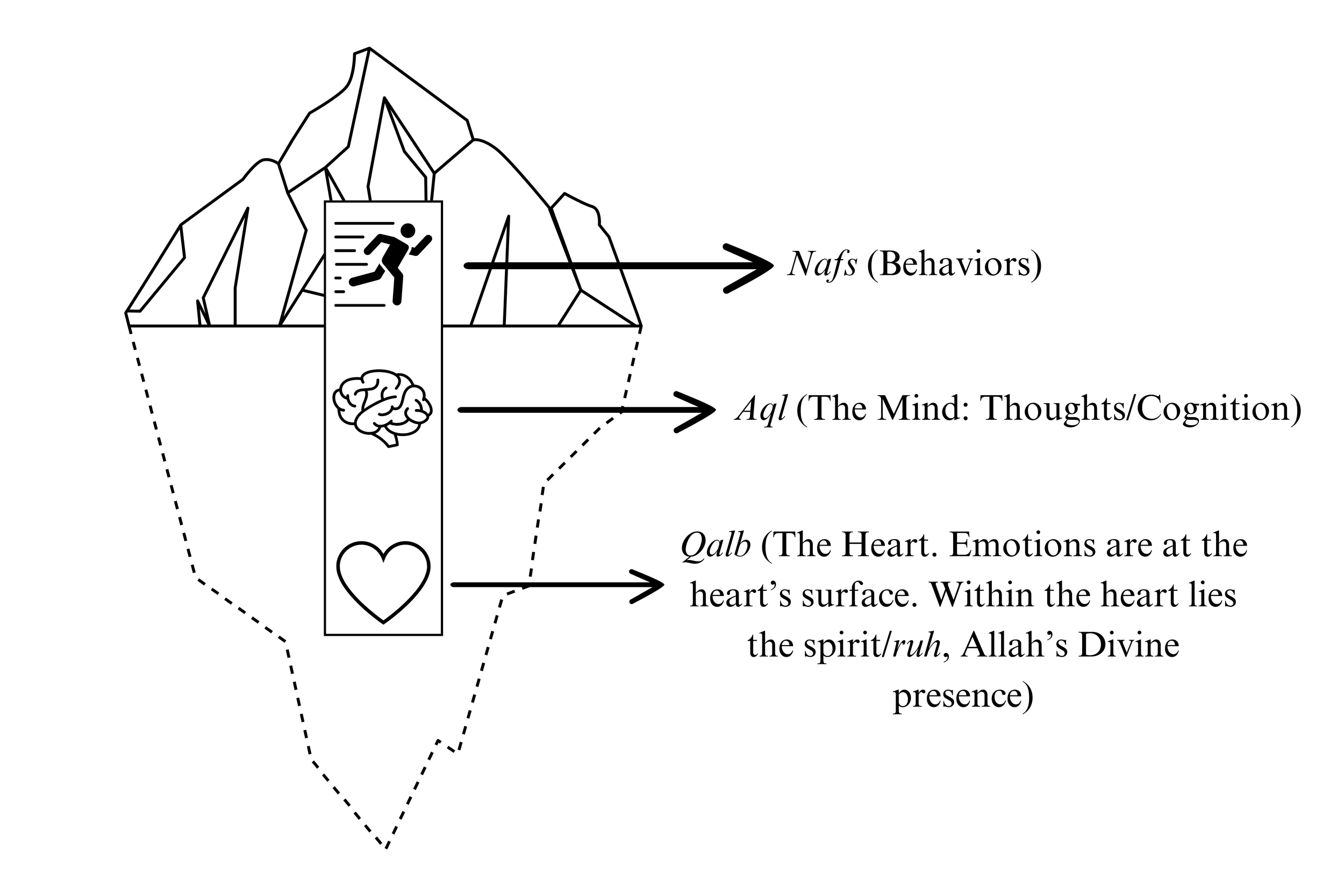

In Islamic psychology, the soul is not a single-layered entity. The qalb (heart), nafs (soul/behaviors), ‘aql (intellect), and ruh (spirit) interact in continuous motion. We behave from this entire inner system, not only from cognitive knowledge. When a teenager seeks connection, it is not an intellectual mistake — it is an expression of the heart’s inclinations, the nafs’s vulnerabilities, and the emotional longings emerging from their developmental stage.

An adapted figure depicting Rothman and Coyle’s (2020) Islamic Model of the Soul

What is also missing from the video’s framing is a truthful acknowledgment of where sexual desire and attraction originate within the inner architecture of the soul. In Islamic psychology, these feelings arise from the nafs al-ammārah — the part of the self that inclines toward impulse, intensity, and immediacy. Within this dimension lives shahwah, the God-created capacity for sexual pleasure, designed for marital intimacy and for the sacred purpose of procreation. These desires are not evidence of spiritual failure; they are evidence of being human. They require cultivation, containment, and maturation — not shame. And when we focus only on behavior, we miss a profound opportunity to teach young adults about the real work Islam calls us toward: the purification of the heart, the tending of the nafs, the struggle to regulate desire, and the practice of compassionate self-accountability so we do not act on every impulse we feel.

This is the first issue the video bypasses: behavior cannot be reduced to information, instruction, or fiqh. Adolescence is shaped by longing, identity formation, emotional intensity, and a deep desire to be chosen and understood. These realities cannot be disciplined away or neutralized through rule-based education alone. As the Prophet ﷺ said, “Truly, in the body there is a morsel of flesh; if it is sound, the entire body is sound… truly, it is the heart.” (Bukhari, Muslim) What lives in the heart inevitably makes its way into action.

The second issue lies in how compassion was framed. In the video, compassion meant speaking gently and offering permissible options — but compassion remained tethered to behavior: How do we help him end it, formalize it, or avoid sin? The son’s inner landscape — his need for connection, affirmation, companionship — remained unspoken and unaddressed. As if it didn’t matter, yet it’s likely the entire reason he was drawn towards the relationship in the first place. Allah describes the Prophet ﷺ as “deeply concerned for you, gentle and merciful toward the believers.” (Qur’an 9:128) Prophetic compassion was never limited to regulating actions; it was rooted in emotional attunement to support turning of the heart back towards Allah.

The third issue stems from the assumption that Islam is primarily cognitive and behavioral — that if one knows the rules, the soul will follow. Unfortunately, Western/secular psychological paradigms have seeped deeply into the Islamic educational and Muslim mental health space. When we center cognition and behavior alone, we overlook the emotional and spiritual terrain from which choices arise. Allah tells us, “They have hearts with which they do not understand.” (Qur’an 7:179) Understanding is not purely intellectual; it is a function of the qalb — of emotional insight, spiritual perception, and inner awareness.

And the fourth issue — perhaps the most striking — is that the heart (qalb) was entirely missing from the conversation. The qalb is the locus of intention, desire, emotion, meaning, and spiritual turning. Allah tells us, “It is not the eyes that are blind, but the hearts within the chests.” (Qur’an 22:46) Yet the video’s framework treated dating purely as a moral infraction to correct, rather than a sign of an inner longing to be understood, valued, or connected. The mothers guided through rules and consequences, not through emotional inquiry, spiritual meaning-making, or compassionate exploration of what was happening inside their sons.

And this absence matters — because when the heart is ignored, guidance remains partial. Behavior may shift temporarily, but the inner world remains untouched. The longing that drew the young person toward the relationship in the first place remains unaddressed, becoming yet another unspoken chapter in the story of their soul.

The First Example Reveals Another Gap We Rarely Name

There is also something profoundly important — and profoundly overlooked — in the first scenario of the video. The mother in that story concludes that her “hands are tied” because she and her husband did not teach their son the religion while he was growing up. Her conclusion is presented as both reasonable and inevitable: if you didn’t plant the seeds early, you have no moral authority to intervene later.

But this framing is incomplete.

From an Islamic psychology lens, even without formal religious education in the home, this mother still had meaningful options — options rooted in relationship, emotion, and the heart, not only in theology. Her sense of helplessness was not because she lacked a religious foundation; it was because her only framework for intervention was a theologically centered, behavior-focused one. Within that narrow frame, she was right: she couldn’t suddenly appeal to Shariah or halal/haram in a house where those categories were never emphasized.

But this does not mean she couldn’t appeal to her son’s inner world, his emotional needs, his longing for connection, or his emerging relationship with Allah as a young adult who had reached puberty — and therefore had entered a stage of direct spiritual accountability. A soulful approach would have allowed her to support and guide him without needing decades of prior Islamic instruction.

She could still have asked:

What does this relationship mean to you?

What are you seeking or experiencing through her?

What feels good, comforting, or grounding in this connection?

Have you thought about where Allah is in your life right now — not in a rule-based way, but in a relational, heart-based way?

She could have guided through attunement rather than authority, inviting her son into a conversation about desire, belonging, attachment, and spiritual meaning — all of which are universal, even without religious literacy.

This also reveals a deeper issue in the video’s entire framing: Where are the fathers? In both stories, the emotional and moral labor falls solely on the mothers, as if fathers are peripheral to their children’s inner worlds. Whether the parents are married, divorced, or co-parenting, a teenager’s spiritual and emotional life is shaped by the relational presence of both parents, not just one. The absence of the father’s voice — his emotions, guidance, or struggles — further narrows the conversation and reinforces a pattern in our communities: mothers are expected to carry the weight of both compassion and correction, while fathers remain unnamed. And of course, there are situations in which a father is absent due to necessity, such as when domestic violence has occurred or is occurring; in those families, safety must always take precedence, and limiting a father’s access is a protective and essential choice. But outside of these painful and important exceptions, the broader pattern persists: we place the full emotional responsibility on mothers and rarely ask how fathers can share, support, or shape the soulful work of guiding a child’s heart.

A more holistic approach would recognize that both parents carry responsibility for their child’s heart, emotional life, and spiritual development. And even in families where the father is absent or disengaged, naming that absence matters. It shapes the child’s inner world, their experience of love, their search for connection, and the meaning they attach to relationships.

In other words, the first mother’s hands were not tied because she lacked theological credibility; they were tied because her framework for intervention was limited to theological correction. A soulful approach — grounded in the heart, the nafs, emotion, developmental needs, and the living relationship between a young person and Allah — would have offered her a way forward. One that did not rely on the past, but on the present moment, the present heart, and the present possibility for guidance, connection, and spiritual anchoring.

What a Soulful, Islamic Psychology Approach Would Offer Instead

When we move beyond the behavioral framing of the video and step into an Islamic psychology lens, the entire conversation shifts. It becomes wider, deeper, and far more human. We begin to see not only the young person’s actions, but the condition of their inner world — the state of their qalb, the stirrings of their nafs, their longings, their vulnerabilities, their spiritual questions, and the tender uncertainty of being newly accountable before Allah while still learning how to regulate their emotions.

Puberty, in our tradition, is not simply a biological marker — it is the beginning of direct responsibility before Allah. This moment is spiritually momentous and psychologically complex: a young soul now stands before God with accountability, while emotionally, neurobiologically, and relationally, they are still in formation. Their desires intensify, their need for belonging expands, and their sense of self feels fragile and unsteady. If parents do not see this intersection — this sacred, complicated threshold — they miss what their children are actually navigating.

A soulful approach begins here. Not with rules, not with fear, and not with “three choices” — but with an intimate understanding of the heart.

1. It begins with understanding, not correction

A soulful Islamic response meets a young person at the level of their lived experience. Instead of beginning with what must stop, it begins with what is happening inside. This shift is essential, because in Islamic psychology, the heart is the center of meaning — the place where inclinations form and where Allah looks. The Prophet ﷺ said, “Allah does not look at your outward form or appearances, but He looks at your hearts and your deeds.”

Understanding must come before correction because without understanding, there is no true relationship — only reaction.

A soulful approach invites thoughtful, spacious questions such as:

Tell me what this relationship has meant to you.

What feelings did it give you that felt comforting or stabilizing?

What were you longing for at the time — connection, affirmation, excitement, companionship, escape?

What did it feel like inside your heart when you were with her?

Where was Allah in your experience of all of this — close, distant, forgotten, confusing?

This approach teaches young adults something our community often neglects: that their feelings are not sinful. Attraction, desire, longing, and vulnerability come from the nafs al-ammārah and its natural impulses — not from moral failure. Shahwah is part of the human design, given for sacred expressions within marriage. To feel desire is not wrong; to learn how to manage it with compassion, courage, and self-accountability is part of spiritual growth.

Beginning with understanding gives the young person a profound gift: the experience of being seen. And when the heart feels seen, it begins to soften, open, and reflect — which is the ground where change grows.

2. It treats compassion as emotional presence, not gentle behavioral correction

In the video, compassion was framed as gentle speech and avoidance of harshness. But compassion in Islam — the Prophetic compassion — goes far deeper. Compassion (rahmah) is emotional presence. It is the willingness to stay close to someone’s complexity, not only their behavior. It is the courage to sit with their pain, their confusion, their longing, and their guilt without immediately rushing to fix, instruct, or warn.

We see this in the well-known teaching moment when a young man came to the Prophet ﷺ and asked for permission to commit zina (unlawful/premarital sexual activity). The Prophet ﷺ didn’t shame him or react with shock. Instead, he engaged him with empathy, inviting him to see the situation from multiple angles, and then — crucially — he placed his blessed hand on the young man’s chest and prayed for Allah to purify his heart. This story is a masterclass in emotional-spiritual presence: the Prophet ﷺ responded not to the behavior alone but to the emotional and spiritual layers underneath.

A soulful approach requires parents to follow this Prophetic model — to become a place of refuge for their children, even when the conversation is uncomfortable. It asks parents to regulate their own fear, disappointment, or anxiety so they can meet their child with steadiness and care. Compassion becomes a way of holding the child’s inner world so that guidance can land in a receptive, softened heart rather than a defended one.

3. It integrates theology, ethics, and spirituality — and anchors abstinence education within a soulful model of sexual health

When we talk to young people about relationships using only fiqh — without ethics, without emotional understanding, without spirituality — we give them a thin, brittle understanding of the religion. We offer them the what without the why or the how. And without those layers, guidance cannot reach the heart.

In my book, I write about three core concepts that form the foundation of a soulful, holistic understanding of sexual health: theology, ethics, and spirituality. These three dimensions always work together. They are not separate silos, and they are not meant to be taught in isolation. When we separate them, we lose the depth our tradition offers.

Theology: The Divine Boundaries and the Orientation of Taqwa

Theology gives us the what — the Divine guidance that frames sexuality as a natural, sacred, and purposeful part of life. It roots sexual ethics in the Qur’an and sunnah, and distinguishes between theology (the why behind God’s commands) and fiqh (the specific rulings). Theology also introduces taqwa not as fear-based compliance, but as reverential love, accountability, and awareness of Allah.

Theology teaches that abstaining from premarital intimacy is not suppression — it is spiritual alignment, a commitment to protect our hearts and preserve the sanctity of intimacy for a context rooted in mercy, trust, and commitment. But theology alone cannot hold a teenager through longing, desire, or heartbreak. It must be paired with…

Ethics: The Virtues, Responsibilities, and Boundaries That Shape the Soul

Ethics (akhlaq) takes us deeper into the why. It teaches that sexual health is not just a private matter between a person and Allah, but also a moral responsibility toward others. It includes honesty, justice (adl), balance (mizan), self-discipline, and the purification of the heart (tazkiyat al-nafs).

Ethics invites young people to ask:

What does it mean to treat another person with dignity and not use them to soothe my loneliness?

How do I honor someone’s rights, boundaries, and vulnerability?

How do I behave with integrity when my nafs wants relief or connection right now?

This ethical grounding transforms abstinence from a rule to a practice of virtue, where self-restraint becomes an act of worship and self-respect.

But even ethics cannot guide the soul without…

Spirituality: The State of the Heart and the Presence of Allah

Spirituality is the how. It centers the qalb (heart) as the place where spiritual insight, emotions, longing, and discernment live. It brings in ihsaan — the awareness of Allah’s nearness — and frames sexual health struggles as opportunities for purification, not as evidence of moral deficiency.

Spirituality teaches young people that:

Sexual desire is part of the nafs al-ammārah, designed by Allah

Emotions are signposts on the path of the soul

Mistakes are invitations to turn back, not to collapse into shame

Allah meets them with mercy, not disgust

Purification of the heart (tazkiyah) is a lifelong process

When we add spirituality, we give teenagers the tools to face their desire without fear, their mistakes without despair, and their future with hope.

The Soulful Model of Sexual Health: Spiritual, Emotional, and Physical Foundations

After exploring theology, ethics, and spirituality in my book, I introduce a Soulful Model of Sexual Health — a holistic framework grounded in the Islamic understanding of the soul and in the connection between belief, emotion, and embodiment.

The Soulful Model of Sexual Health for Muslims (Qureshi, 2025)

The model shows that sexual health is never only physical — it rests on three interwoven foundations:

1. Spiritual Health (the Heart of It All)

Sexual health begins with the heart’s relationship with Allah — its intentions, its desires, its longing for closeness, its struggle with the nafs. When intimacy in marriage is viewed as ibadah, and when abstinence is understood as self-discipline rooted in reverence, sexual ethics come alive with meaning. This layer cultivates:

Taqwa (reverential awareness of Allah)

Intentionality

Purification of the heart

Ihsaan (striving for excellence in one’s inner life)

2. Emotional Health (the Landscape of the Qalb)

Emotional health acknowledges that the qalb holds wounds, memories, shame, hopes, and attachment needs. Without addressing these emotional realities, teenagers will turn to relationships not from clarity, but from ache. Emotional health supports:

Processing shame, guilt, fear, longing and other emotions

Developing self-awareness of one’s emotions

Understanding the root causes of relational needs

3. Physical Health (Honoring the Amanah of the Body)

The body is a trust (amanah) from Allah, deserving of care, protection, cleanliness, and balance. Physical health includes hygiene, sleep, nutrition, reproductive knowledge, and bodily awareness — all of which lay the groundwork for healthy intimacy later. It reflects the prophetic teaching: “Your body has a right over you.”

Soulful Parenting for Premarital Abstinence

When these foundations—spiritual, emotional, and physical—are nurtured early, premarital abstinence becomes a natural expression of inner integrity, not an externally imposed fear. Parents play a crucial role here. Soulful parenting cultivates:

Spiritual grounding

Emotional intelligence

Body awareness

Ethical decision-making

Compassionate self-accountability

This approach helps young people abstain not because they fear hellfire, but because they value:

Their heart

The wellbeing of the other person’s soul

Their relationship with Allah, even through struggles

The sacredness of their body

A soulful model teaches young Muslims how to live sexual ethics — not just obey them.

4. It centers the qalb — the heart — as the locus of transformation

A soulful approach recognizes that real change does not begin with behavior; it begins with the heart. The heart is the seat of intention, meaning, desire, and spiritual turning. It is also where emotional wounds live. If a teenager feels unseen, lonely, insecure, or unworthy, no amount of fiqh will address that root.

A soulful approach asks parents to inquire gently:

What is your heart struggling with right now?

What longing were you trying to soothe?

What are you afraid of?

Where does your heart feel disconnected?

What do you need to feel close to Allah again?

When these questions are explored honestly, the heart naturally begins to open to Allah. Tawbah (repentance) becomes not a reaction to fear of consequence but a turning back driven by sincerity and inner clarity.

5. It acknowledges the spiritual–developmental struggle of puberty

Puberty is one of the most misunderstood and under-discussed transitions in Muslim families — even though it is a central turning point in both Islamic law and the Islamic psychology of the soul. In our modern context, we often speak about puberty only in biological terms: the hormonal shifts, the changes in the body, the increasing awareness of desire. And while this perspective is valid, it is only the beginning.

As I wrote in Soulful Sexual Health for Muslims, the American Psychological Association defines puberty as “the stage of development when the genital organs reach maturity and secondary sex characteristics begin to appear.” In other words, puberty marks a biological transformation signaling the beginning of adolescence. Islam, however, does not have an equivalent concept of “teenager” or “adolescence.” These are Western developmental categories. What Islam does offer is something far deeper: a spiritual framework for understanding this transformation. Puberty — bulūgh — represents the moment a child becomes spiritually accountable before Allah. It is the point when the inner landscape of the soul, with its nafs, emotions, desires, impulses, and intentions, becomes directly tied to responsibility before God.

The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ taught, “The pen has been lifted from three… the child until he reaches puberty.” This moment signals the beginning of spiritual adulthood — not because the child suddenly becomes emotionally mature, but because their soul is now capable of moral intention.

Islamic tradition recognizes that the signs of puberty differ for girls and boys: menstruation, nocturnal emissions, or — if these do not occur earlier — the age of 15. At this threshold, the angels known as kirāman kātibīn begin recording deeds. The Qur’an states:

“Indeed, over you are keepers, noble and recording; they know whatever you do.” (82:10–12)

This moment, often taught with fear, is actually a moment of immense Divine compassion. Allah knows the emotional turbulence, the volatility of desire, the fragility of self-esteem, and the intensity of social pressures that characterize this time. He knows the nafs al-ammārah (the soul that commands to evil) is awakening, that shahwah (sexual desire) is gaining strength, that peers become central, and that the heart is still tender, still forming, still learning how to orient itself toward Him.

This is why in Islam, puberty is not merely biological — it is a sacred invitation to compassionate self-accountability. It asks the young person:

· How will you tend your heart as it learns to navigate desire?

· How will you understand and manage shahwah without shame?

· How will you hold yourself gently when you stumble?

· How will you return to Allah when emotions overwhelm you?

A soulful approach honors this sacred tension: a teenager is now spiritually accountable, yet psychologically still becoming. This tension is not a flaw — it is the divine design of spiritual growth. It means that the spiritual path is meant to begin in complexity, not clarity — with compassion, not condemnation.

When parents recognize this, everything changes. Instead of reacting with panic when desire shows up — or worse, pretending their child is “too young” to feel it — parents can guide with the tenderness Allah calls for during this stage. They can help their teens develop a framework of compassionate self-accountability, where they learn to manage desire without shame, to understand their emotions without judgment, and to take responsibility for their choices without feeling spiritually ruined.

Without this, young Muslims grow up — as many of us did — with a distorted view of accountability, one rooted in fear, secrecy, and overwhelm. But with it, they learn that Allah’s gaze upon them is not a gaze of threat, but a gaze of nearness: one that guides, steadies, and accompanies them through the most vulnerable years of their soul’s formation.

6. It requires parents to confront their own discomfort — and do their own inner work

This is the hardest part of a soulful approach — and the reason many parents avoid it. It requires parents to look inward, to notice:

Their own fear of what people will say

Their own shame around sexuality

Their unresolved wounds from their own adolescence

Their tendency to control behavior when they feel powerless

Their difficulty tolerating complexity or emotional expression

Their limited models of parenting from their own childhood

Their discomfort with discussing sexual desire, attraction, and spiritual struggle

A soulful approach asks parents to hold themselves accountable, too — to soften their hearts, to sit with their discomfort, to learn emotional regulation, and to name their fears so they do not project them onto their children. Parenting becomes an act of inner purification for the parent as much as for the child.

7. It guides through relationship, not regulation

Most importantly, a soulful approach understands that guidance is not transmitted through rules alone — it is transmitted through relationship. A child who feels safe will reveal their heart. A child who feels seen will seek support. A child who feels loved will trust their parent enough to come back to Allah with sincerity.

Regulation tells a child what to do. Relationship teaches them who they are.

Regulation may stop a behavior. Relationship transforms a heart.

And in Islam, it is the heart that Allah looks at.

Summary and Conclusion: Returning to the Heart, Even When It’s Uncomfortable

When we gather all of these threads — the gaps in the video, the missing emotional layers, the absence of the qalb, the reduction of Islam to rules and consequences — a clearer picture begins to emerge. What appeared at first to be a compassionate, honest handling of a “taboo topic” was in fact a narrow, behavior-centered interpretation of a much more complex reality. Young people entering relationships are not simply breaking rules; they are navigating the terrain of their souls — their nafs, their emotions, their longing for attachment, their search for identity, and their early steps into direct accountability before Allah.

A soulful Islamic psychology approach asks us to meet our children in that terrain — not reactively at the level of behavior, but proactively at the level of the heart. This requires us to slow down, to understand, to stay curious, and to see the human being in front of us rather than the rule they broke. It requires us to integrate theology with ethics, spirituality, and emotional attunement. It calls us to guide not through fear of punishment, but through love, reverence, and the kind of God-consciousness that softens the heart rather than constricts it.

This is where we must also recognize the profound difference between two kinds of “fear of God.” One is psychological fear — the dread of punishment, rejection, wrath, or divine anger. It constricts the heart and often pushes a person into hiding, secrecy, or shame. It can make God feel distant, severe, and unapproachable. The other is reverential fear, the kind rooted in love, awe, and deep consciousness of Allah’s majesty and mercy. This fear softens, opens, and transforms. It draws a person nearer. It emerges when the heart feels held by Allah, not threatened by Him. And it is this kind of fear — born of love, anchored in reverence — that truly guides a young person through desire, confusion, heartbreak, and longing.

But this approach comes with a truth that many parents find uncomfortable: it requires much more of us. It asks us to enter conversations without the safety of black-and-white moral directives. It asks us to tolerate ambiguity, to sit with the parts of our children’s experiences that we don’t understand or that trigger our own fears. It asks us to resist the urge to control behavior when what is needed is connection. And it asks us to do our own inner work — to tend to our own fears, our own histories, our own relationship with Allah, our own emotional patterns — so that we can meet our children with spaciousness rather than reactivity.

A soulful approach does not mean abandoning boundaries or Islamic ethics. It means grounding those boundaries in tenderness, wisdom, and attunement. It means remembering that the heart is where real transformation begins. And it means trusting that when we guide our children through compassion that sees the whole soul — not only the behavior — they can return to Allah in a way that feels chosen, not coerced; loved, not shamed.

This is the deeper conversation missing from videos like this one— and from so many Muslim discussions about dating, relationships, and adolescence. If we want our children to navigate intimacy with integrity, faith, and self-awareness, we must offer them more than rules. We must offer them relationship, emotional safety, and guidance that honors the complexity of being a young soul in a world that is constantly pulling at them.

This is the heart of what I explore in Soulful Sexual Health for Muslims. If you want to delve deeper, the chapters on abstinence, the search for a spouse, and soulful parenting for sexual health expand on these themes with frameworks, reflection questions, and pathways toward a more holistic understanding.

Our children deserve an approach that doesn’t just tell them what is right, but teaches them how to understand themselves — how to navigate longing, how to honor their hearts, and how to find their way back to Allah with love.

References

Qureshi, S. (2025). Soulful sexual health for Muslims: A developmental approach for individuals and clinicians. Routledge.

Rothman, A. & Coyle, A. (2020). Conceptualizing an Islamic psychotherapy: A grounded theory study. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 7(3), 197-213.